August 9, 2025

Prechter’s Reply to Anonymous Critique Posted on Substack on July 1, 2025

I welcome the opportunity to defend and expand the case for Thomas Nashe as a pen name of the Earl of Oxford. The aim of this reply is to inform and perhaps entertain the intellectually curious.

This is an essay, not a paper. References cited in my book (Oxford’s Voices) and paper on Nashe for The Oxfordian (link in Appendix 3) or in the critique are not necessarily repeated. The point here is to assess the validity of the critics’ arguments. I respond here to all their points, substantive and trivial.

The critique to which I am responding came in three parts. The author of Part 1 is careful and sticks to narrow points. The author of Part 2 presents shallow arguments, easily refuted. The author of Part 3 seems to be genuinely trying to figure things out under the old paradigm.

I don’t care that these critics decided to post anonymously. Perhaps one reason is that they have authored papers and articles, too, and wish to avoid the risk of having someone perform a hatchet job on them. The identities of the critics are not hard to figure out (I didn’t do authorship research for 25 years for nothing), and I can assure you that dismantling some of their published claims would not take much effort.

Nevertheless, my focus is on defending my case, not attacking them. So, let’s get going.

Who Am I?

Like most people involved in the authorship question, I am not a full-time academic researcher. I run a publishing company that employs 70 people. I have written books on finance and social-mood theory, co-authored papers for financial and social science journals, spoken at universities and conferences, and penned market analysis for 46 years. I have a family and a couple of hobbies. (www.robertprechter.com/bio)

I have also spent 25 years researching Elizabethan-era authorship. I think I have correctly assessed who wrote what when it comes to poems, stories and plays of the era. I believe I figured out something no one else did: the names other than Shakespeare under which the Earl of Oxford wrote. On the flip side, I have identified over a hundred items that various Oxfordians have attributed to Oxford that I am sure he did not write. As a foil and check, I examined 350 writers of the era who, I believe, wrote their own material. Along the way, I found five other Elizabethans who wrote under pen names. You can learn about the project at www.oxfordsvoices.com. Earning my infinite gratitude, a group of supporters tired of the toxic environment at a certain Facebook page created the Oxford’s Allonyms group on Facebook, where courteous discussion, debate and contributions are welcome.

I am proud to be thinking outside the box. Many breakthroughs have been discovered by outsiders. J.T. Looney figured out who Shakespeare was. He made a couple of mistakes, such as arguing that Shakespeare was not the author of The Tempest. It can happen when you are breaking new ground.

As Galileo commented, “All truths are easy to understand once they are discovered; the point is to discover them.” I think Oxford’s Voices (OV) postulates a new truth, which is that the Earl of Oxford wrote under many names, Shakespeare being a latecomer in the progression.

Among Oxford’s Voices, I include the celebrated Thomas Nashe. Of all the names under which I concluded Oxford wrote, Nashe was the most challenging to establish.

The question at hand is, did I make a big mistake when it comes to Nashe? I don’t think so. If anything, answering the critics has just made my thesis stronger.

Conundrums on Both Sides

On the question of Thomas Nashe’s actuality, each side faces a serious conundrum:

Traditional biographers must account for why Nashe and the Earl of Oxford (both as himself and Shakespeare) are intimately intwined in both language and concerns, without a notable difference between them.

The thesis that Nashe is a pseudonym must account for why there is a paper trail indicating a life associated with the works that came out under the name Thomas Nashe.

I do not believe biographers of Nashe have adequately dealt with the first conundrum. A few of them expressed dismay over it. Most of them did not address the question.

I dealt with the second conundrum head-on. I have interpreted the Thomas Nashe biography in a unique and consistent way, offering a coherent picture.

I perceive no alternatives. The idea that Nashe is allonym doesn’t work beyond the possibility that Oxford borrowed Nashe’s name from a University of Cambridge butler or an unremarkable man from Lowestoft. The life of Nashe the writer, it seems to me, is either fully valid or fully manufactured. I think it’s the latter.

A Brief Overview of the Oxfordian Case for Nashe

It is crucial to point out that when people observe how often Nashe and Shakespeare think and sound alike, they are really observing how much Nashe and the Earl of Oxford think and sound alike. That fact can slip even an Oxfordian’s mind when people refer to “Shakespeare” in the context of a discussion about Nashe.

Oxford’s Concerns Are Nashe’s Concerns

As noted in my TOX paper, Thomas Nashe exhibits obsessive concerns over matters relating to the Earl of Oxford, stretching back years and including obscure details of Oxford’s experiences and the lives of his relatives, both living and dead.

Nicholl reported that in Pierce Penilesse (1592), Nashe by way of an animal fable “precisely allegorized” events at the highest levels of society leading to the execution of Oxford’s beloved elder cousin, the Duke of Norfolk in 1572. Nicholl mused, “‘Alas, goodly Creature’ [is] a curiously poignant epitaph for a Catholic who had been executed for treason.” The term is Oxford’s: “Goodly creature” appears in Pericles (IV,i), and “goodly creatures” appears in The Tempest (V,i).

Oxford’s deceased poetic uncle, the Earl of Surrey, wrote Nicholl, is “featured prominently and approvingly in The Unfortunate Traveller,” where Nashe “praises Surrey unstintingly.” Surrey pioneered the Shakespearean sonnet form, which Oxford adopted.

Over three separate pamphlets, Nashe defends the Earl of Oxford against disrespect shown by Gabriel Harvey, citing his Audley End speech of 1578 and his Speculum Tuscanismi poem of 1580. Even here, there is a linguistic link to Oxford. Nashe over two pamphlets refers to Harvey as “this Thraso” — a braggart — with his “Thrasonimse,” and Oxford (as Shakespeare) describes the braggart Armado as “thrasonicall.”

Nashe’s skit, Summers Last Will and Testament, caricatures Oxford’s father-in-law, his brothers-in-law and himself. It evidences knowledge of details in Lord Burghley’s will, which did not come to light until Burghley’s death in August 1598. Rita Lamb understood that parody was involved but could not fathom how Nashe got away with producing the play, much less publishing it eight years later, “without a flicker of response [and] no record, or even report, of Nashe being formally punished.” In the play, the character Vere admits to having dissipated “all my flowry treasure, and flower of my youth…spent on good fellows, in these sports,” meaning plays. In a 1601 letter to Robert Cecil, the Earl of Oxford used similar words: “yf yt shall pleas her Magestie in regard of my youthe tyme & fortune spent in her Courte….”

Nicholl wrote, “Nashe [knew] two of the Oxonian ‘Wits’ particularly well: John Lyly and Thomas Watson.” No historical record places Nashe with either man, but connections to Oxford are direct: John Lyly was Oxford’s personal secretary, and Watson dedicated his only book of English poetry, Hekatompathia, to the Earl of Oxford.

Oxford (as Shakespeare) and Nashe dedicated works to the Earl of Southampton in 1593-1594, then stopped. Southampton was being encouraged to marry Oxford’s daughter Elizabeth until late 1594.

Oxford’s Language and Nashe’s Language Are Intimately Intertwined

As also noted in my paper, scholars have made some stunning statements about the linguistic parallels peppering the works of Oxford and Nashe. McCarthy summarized Tobin’s observations:

[Stylistic parallels are] distributed over almost the whole of Nashe’s oeuvre and many of Shakespeare’s histories and comedies[, including] Titus Andronicus, Richard III, Henry IV, Henry V, Julius Caesar, Troilus and Cressida, Macbeth, Romeo and Juliet, Merchant of Venice, Hamlet, Othello, King Lear, All’s Well that Ends Well, Measure for Measure [and] Merry Wives of Windsor. (McCarthy 146)

J. Dover Wilson…said in conclusion that he could not account for them…. (McCarthy 146)

Nashe is so much a part of the fabric of Shakespeare’s works that it is not too much to say that Shakespeare without Nashe and his works would not be Shakespeare. (Tobin 109)

One of McCarthy’s comments links these overlaps to shared emotional states:

It is hard to imagine the process by which scraps of five of Nashe’s works keep floating into Shakespeare’s head, and eventually forced their way into the diction of [Hamlet] with such huge freight of apparently personal emotion…. (McCarthy 149)

Personal emotion suffuses Nashe’s treatment of matters of deep meaning to the Earl of Oxford, as cited above relating to his deceased cousin, his deceased uncle and his enemies. The parallels are not only linguistic but also ideational.

So, Oxford and Nashe think the same, write the same, and feel the same. Oxford and Nashe are akin to married people who finish each other’s sentences.

Shared Language Extends to Other Voices

How many times might you think my book (OV) refers to Nashe outside the Nashe chapter? A handful? The answer is: over 2400 times. It takes reading the entire book to understand how intricate the literary relationships are between the Nashe persona and other Voices. Those observations form the tapestry of my case. OV covers the equivalent of 6000 normal-sized book pages. Obviously, not everything I have observed about Nashe will fit into a journal paper or a chapter, and I am sure you don’t want me to insert 250 pages here to make the point. Appendix 2 provides examples of textual overlaps with two other Voices just to give you a flavor.

In Shakespeare’s Books (p.310), Stuart Gillespie refers to “…Shakespeare’s acquaintance with Nashe in echoes of rare or otherwise distinctive words and phrases.” They show up even in places no one would expect, including two instances of private correspondence and a purported reminiscence by Nashe about his childhood (see discussions below).

A Quiz

Two books attributed to different authors in the Elizabethan era prompted identical stylistic assessments from critics. Can you guess which books they are talking about?

One scholar cited a book for these traits:

“a gift for energetic doggerel,”

a “weird and piquant vocabulary [like] Lewis Carroll,”

a “jaunty and comic” tone

and “a rugged English gusto.”

Compare those descriptions to what another critic wrote about another book, line by line in order:

“he indulges his own kind of scribbledehobble,”

“the nonce words come thick and fast [in this] dazzling piece of apparent jabberwocky,”

conveying a “zestful humour”

with “the full vigor of the English language….”

Isn’t that correspondence remarkable?

Neither scholar quoted above indicated that he knew of the other’s assessment. Nor would the two critics have thought to check each other’s assessments because the first scholar was writing more than three decades after the second, about a book that was written more than three decades before the first. Did you guess the books correctly?

The first book, described by J.F. Nims in 2000, is Ovids Metamorphoses (1567), attributed to Oxford’s uncle, Arthur Golding.

The second book, described by J.B. Steane in 1972, is Lenten Stuffe (1599), attributed to Thomas Nashe.

I think the two books are stylistically similar because they were written by the same man. The Earl of Oxford completed the first exercise when he was 17 years old (article link in Appendix 3) and the second one at age 48.

No other writers of the Elizabethan era exhibit the same degree of sustained wordsmithing panache. Most other writers’ material was comparatively conservative, if not leaden. Oxford’s talent in this regard (as in others) was unique.

Conclusion

The two names — Nashe and Oxford — belong to conjoined twins. The cavalier suggestion that a real Nashe simply copied or absorbed Oxford’s stylistic ways does not work (see below). The most elegant and parsimonious explanation for their close correspondence is that one person is doing the writing.

On Context

Numerous scholars have remarked upon Shakespeare’s literary debt to John Lyly. Do you really think the greatest master of language the world has ever known (Oxford, as Shakespeare) learned the complex and innovative literary technique known as euphuism from his secretary? If you doubt it, and if you think Oxford might have written the two Euphues books that came out in John Lyly’s name, you have cracked open the door to Oxford’s Voices.

Do you think it reasonable that John Lyly wrote two groundbreaking prose novels about Euphues in 1578 and 1579, causing a court craze, and then, despite living another quarter century, never wrote another? And that a newcomer named Robert Greene took over immediately in 1580, continuing the progression of prose novels, one of which features Euphues? If you think that shift is odd, you have opened the door to Oxford’s Voices.

Do you think it strangely convenient that after Robert Greene’s mock death in print, Thomas Nashe took on Greene’s fight against the Harvey brothers, carrying on the satirical approach Greene used in his late pamphlet, Quip for an Upstart Courtier? If so, read on.

Scholars have proposed that Shakespeare (Oxford) stole ideas, plots and language from Lyly, Greene and Nashe. But Oxford’s publishing activity has been traced back to 1560 (Precher, TOX, 2007) and his playwriting activities back to 1562 (Jimenez, TOX, 2004), so Oxford is the progenitor in all three cases. Do all four names (Lyly, Greene, Nashe and Shakespeare) belong to independent writers who steal from predecessors in an orderly progression? Or is one man behind them?

Gabriel Harvey recognized the progression described here by calling “Nashe, the Ape of Greene; Greene, the Ape of Euphues.” He continues with, “Euphues, the Ape of Envie” (which Oxfordians might recognize as a homonym for N.V., or Ned Vere). Harvey concludes with a summary: “the three famous mammets of the press, and my three notorious feudists, drawe all in a yoke.” Have you looked up the word mammet? Here is the definition, from Google AI:

“Mammet” is an obsolete English word, now primarily found in historical or literary contexts. It can refer to a false god or idol, or more commonly, a doll, puppet, or effigy, like a scarecrow.

Lyly, Greene and Nashe, says Harvey, are puppets and scarecrows.

In A New Letter of Notable Contents (1593), Harvey conflates four literary personae of the Earl of Oxford:

[They may] wonder how Machiavell can teach a Prince to be, and not to be religious? [who] within few moneths is won, or charmed, or inchaunted, (or what Metamorphosis should I terme it?) [and] whom shall he cunnycatch…?

He joins Nashe (as Machiavelli), Shakespeare (referencing Hamlet), Arthur Golding (referencing Metamorphoses) and Robert Greene (whose name is on four pamphlets about “cony-catchers”).

One of our critics (Anon3) tries to accommodate such statements by adopting the proposal that a real-life Nashe may have been writing “on behalf of a crew of writers who were associated with de Vere.” That idea does not pan out well, because although the standard story has Greene and Nashe working nose to nose on pamphlets such as Menaphon, Quip and perhaps Groats-worth, Nashe testifies in Strange Newes that he had met Greene in the past “only for a carowse or two” and had “not seene him [for] two yeares”!

What is all that about? Someone is lying, and that someone, as Anon3 concedes, is “associated with de Vere.” What I think happened is that Oxford dispatched his pen name Greene partly in response to Harvey’s threat of a lawsuit (see more below), and he did not want anyone looking for Nashe to get information about Greene. So, he had Nashe say they weren’t close.

Our critics take various orthodox stories for granted, missing hundreds of fine points that produce internal contradictions. When examined, the fine points fit my paradigm better than theirs.

In the Context of Oxford’s Voices, Many More Mysteries Evaporate

It is crucial to understand how intimately other Voices are linked to Thomas Nashe and how those links reveal what is going on. Here is but one of a hundred examples provided in OV:

In Christes Teares (1593), Nashe writes to Lady Elizabeth Carey, “To the eternizing of the heroical family of the Careys, my choicest studies have I tasked.” Nashe’s comment does not fit the orthodox context. McKerrow (p.215) admitted, “Nothing of the kind…is known.” Think for a moment what a staggering admission that is. Nashe says he had dedicated his choicest studies to the Careys, yet Nashe’s most dedicated biographers cannot find any trace of them. Where are they?

In my context, all is crystal clear. William Warner (another name with no bio) had dedicated Pan his Syrinx Pipe (1584) to George Carey and Albions England (1586) to Henry Carey. Robert Greene had dedicated Orpharion (1588) to Robert Carey. Thomas Lodge had dedicated Rosalynde (1590) to Henry Carey. Fitting Nashe’s characterization, Albions England and Rosalynde are unquestionably among the “choicest” of all Elizabethan literature.

Observe how Rosalynde links to all the Voices in our chain: the book’s subtitle, Euphues Golden Legacie, names John Lyly’s hero; the book contains a preface by Robert Greene; and Shakespeare dramatized the story in As You Like It. But wait, say critics; we can be sure that Thomas Lodge wrote Rosalynde because Greene tells us Lodge penned this romance while battling storms and surges of sea spray on board a ship in the middle of the Atlantic! If Greene says it, it must be true. Based on the story’s close affinity to Greene’s Menaphon, John Payne Collier proposed that Robert Greene wrote Rosalynde. Be wary of taking a step down that road. If Robert Greene is lying about who wrote Rosalynde, then you can’t trust anything he says, can you?

Nashe is the toughest of all Voices to establish because I had to accommodate the substantial body of evidence implying he was a real person. I think I did a pretty good job of it. My critics think I failed, and they explained why. Come along with me and see how they fare.

The Critique

Three critics contributed to the effort. Privately, I call these shadows Dachau, Dodger and Mahue, but to be polite, in this reply I will just call them Anon, Anon2 and Anon3. Anon2 critiques my paper, and the other two critique a chapter in my book.

Their title is “A Critique of the Theory that Thomas Nashe was a Pseudonym,” but their treatment is far narrower than that. They thoroughly evade the first conundrum described above, which is the bedrock of my argument. Instead, they selectively critique my proposal that evidence for a life for Thomas Nashe can be interpreted in the context of the idea that the name is a pseudonym of the Earl of Oxford. Before moving on to specific responses, we must establish a key point.

Continually Affirming the Consequent

It is important to recognize that the critique is full of comments applying the logical fallacy of affirming the consequent. An example from Anon2 is, “Nashe’s participation in the anti-Marprelate efforts fits very well with him living for a time in Archbishop Whitgift’s home.” Sure, if a real Nashe wrote the anti-Martinist pamphlets. If Oxford wrote them, then he was Whitgift’s guest.

When one engages in that kind of thinking, one neglects to examine the context of a claim. After all, why bother? If the premise is self-evident, so is the conclusion.

Consider the situation that Anon2 takes for granted in the above-quoted statement. The intrusion of Martin Marprelate into English religio-politics was a threat to the survival of the state. De Vere, who had proved himself a consummate wordsmith over a period of years and could be trusted to maintain state secrets, would have been authorities’ natural choice for spokesman. Whitgift is on record later as personally permitting the publication of Venus and Adonis, so we know that he granted special favors to the Earl of Oxford, whom he had known since their shared Cambridge days in 1563-1564.

Would the Church of England have chosen the Thomas Nashe of biography to represent their cause? Our critics evade an inconvenient fact: At the time the Church chose a literary defender, Nashe had not issued a single publication. The first anti-Marprelate pamphlet went out in August 1589 under the name Pasquil. As Grosart assured us, “‘Pasquil’ was everywhere (contemporaneously) accepted as a pseudonym of Thomas Nashe.” Nicholl (p.72) confirmed of Pasquil’s pamphlets, “There is certainly material from Nashe in them….” Yet Nashe’s preface to Robert Greene’s Menaphon, registered the same month, was not yet in print, and his first pamphlet, Anatomie of Absurditie (though registered the year before), did not come out until later that year or early 1590. In short, Archbishop Whitgift would have had little basis for believing at a 21-year-old lad with no published writing to his name was qualified to take on a literary battle of crucial importance to the state.

One should not give critics free passes to claim or dismiss things summarily when the simplest declaration can be encumbered by such a glaring yet blithely unconsidered improbability. This is the kind of thing that occurs throughout the biography of Thomas Nashe, which is what prompted me to take a closer look in the first place.

Every time readers come across a statement such as, “Nashe’s participation in the anti-Marprelate efforts fits very well with him living for a time in Archbishop Whitgift’s home,” they naturally take it as perfectly sensible. Didn’t you? But time and again, it is not.

Now for my replies to the critique.

Anon’s Critiques

Anon’s critiques are by far the best of the bunch. I treat them roughly in the order covered by Anon. I think there are interesting points throughout my replies, but if you care only to hit the highlights, just search on carats (^), and they will take you to the most fun parts. Let’s dive in.

^Carey’s Letter to His Wife

Anon’s first major declaration is, “George Carey’s letter to his wife, when combined with a recognizance found in the Repertory for the Court of Aldermen of November 1593, is nearly conclusive proof that Thomas Nashe was not a pseudonym.” I provided a strong reason not to believe that statement.

Anon purports to present Prechter’s scenario but offers only part of it. He selectively omits the rest, stating, “An evaluation of this speculated scenario has been omitted in this paper; we do not have to parse through the details of this scenario.” Is that so? What exactly does he not “parse”?

Anon omits all five key points on which my proposed scenario about Carey’s letter stands. As explained in my paper and chapter, they are:

(1) Rita Lamb discerned dishonesty in the letter;

(2) Duncan-Jones observed that Carey’s letter to his wife contains striking Nashean features;

(3) Prechter linked the letter’s most colorful phrases to Oxford as Shakespeare;

(4) the letter slips into third person; and

(5) it was written in haste.

Duncan-Jones discerned in Carey’s letter a handful of impressive connections to the writing of Thomas Nashe. As summarized in my paper, “George Carey’s letter emulates Thomas Nashe in rhetoric, poetic expression, coining boisterous words and crafting sophisticated metaphors.” Duncan-Jones made special note of the phrases, “my hors heeles” and “comody-tragedicall.” Naturally in my context, both terms appear in Shakespeare. The first phrase shows up in Henry VI, Part 1 (I,iv) as “my horse’s heels,” and the second one shows up in Hamlet (II,ii) as “tragical-comical.”

The literary aspect of the letter is particularly noteworthy because it is private correspondence. In this case (and probably only in this case), Captain-General George Carey waxes eloquent in the manner of Thomas Nashe and Shakespeare, which is to say Thomas Nashe and the Earl of Oxford. And he manages to do so while writing as fast as his hand can trot. How did that happen? Were Nashe and Shakespeare’s compositional ways second nature to him? I doubt it. Carey wrote bureaucratic memos but issued no creative writing. I concluded that Oxford, in a jolly mood, was dictating a list of excuses to help his friend (whom he had known at least since 1570, when they served in the military briefly against the Scots) explain to his wife why he had to stay away from home.

One way for Anon to counter the idea that Oxford dictated his friend’s letter would be to present some other writing by George Carey that breezily emulates Nashe and Shakespeare. Otherwise, Carey’s letter to his wife must be considered unique in his corpus.

Anon asserts, “Of course, Nashe was found and arrested, at some point before 13 November 1593. Carey writes that Nashe is “there presently in great missery.” But we cannot believe Carey on that point because someone sounding like Nashe composed his letter. Nashe could not have been both present and miles away in a jail cell.

So, is Carey’s letter an element of “conclusive proof” and “definitive evidence” that Oxford was not posing as Thomas Nashe? On the contrary, it serves as an instance in which Thomas Nashe is present where he is not supposed to be, confounding the biographical story. Anon uses the text of the Carey letter to challenge other lines of reasoning in my chapter, but because the veracity of the letter is suspect, the challenges are of no force.

On a minor point, Anon states there is no evidence that Oxford was with Carey at the time. That point is true but of no weight. Oxford’s biography is mostly blank in the 1590s, so there is little evidence of anything he was doing. I think the stylistic aspects of Carey’s letter reveal something he was doing.

Anon also states that Carey’s letter proves that Nashe was receiving money from Carey. That would be true if the letter were genuine. But it is not.

Anon concludes, “The implications of this one document undermine many of the further arguments that Thomas Nashe must have been a pseudonym.” On the contrary, it fits right in.

Quibbles and Bits

Anon says, “There is no supporting evidence provided to establish this scenario, that the London aldermen were informed that Christ’s Tears was written by de Vere.” That is true. I merely proposed that their becoming informed would explain why Nashe escaped punishment for anti-government writing, which in those days was severe.

Anon tries to discredit my assessment of the low probability that Greene and Nashe, both suspected Voices, were recorded as having matriculated at Oxford’s old college of St. John’s. Having studied a good deal about the colleges, he says I should have considered the sizes and entrance requirements for all 32 colleges at Oxford and Cambridge to obtain a precise number of how low the probability was. He says my not having done so is “problematic.” Look how far he goes with this theme:

Again, if one really wanted to perform this calculation, one would have to study what kinds of students were accepted at the various colleges. What purposes did the various colleges serve? What colleges would students like Greene and Nashe have been interested in joining, and would likely have been accepted into?

The overkill here is palpable. How can anyone know what colleges Greene and Nashe would be “interested in joining,” when neither name has any life whatsoever attached to it prior to the matriculation records conveniently appearing at Oxford’s old college? Even if my estimate (which was based on the number of colleges) were to drop from 1 in 1000 to 1 in 500, or even 1 in 200, the coincidence is still remarkable. Anon could have done the calculation himself if he thought it would explain why the low probability didn’t matter. Doing so, however, might have required an explanation from him. Anon challenged my calculation, but he did not challenge the implication.

In discussing the Nayshe family’s low income and therefore inability to pay for a pre-university education, I called William Nayshe “non-ordained” because, as Nicholl wrote, he “was never formally instituted as vicar.” Anon protests: “he was a ‘stipendiary curate’…” meaning a priest or priest’s assistant. The DNB, however, does not say William was a curate. It says, “His father, who is called in the Lowestoft parish register ‘preacher’ as well as ‘minister,’ seems to have been curate there, and never obtained preferment,” which means he was never promoted. Nicholl uses seems as well. I do not know why Anon removes scholars’ repeated term of uncertainty. It is likely, as Anon proposes, that William “was paid an annual stipend.” So, what? Ordained in a lower order or not, his pay was surely small. As Nicholl stated of William’s financial status, “At these lower echelons, the clergy was an impecunious business.” Anon knows all this because my chapter on Nashe includes all these quotes.

A note in W.C.’s Polimanteia mentions that Nashe left Cambridge early. Anon says W.C. would have said so only if he knew that fact from real life. I don’t know the basis for W.C.’s comment, but I do know that he was highly informed about Oxford’s Voices, as discussed in the W.C. chapter of OV. Directly to the point at hand, he knew that the Nashe-Harvey quarrel was in fact an Oxford-Harvey quarrel, as discussed below, and that fact alone negates whatever power Anon thinks W.C.’s comment has.

I pointed out that in the Cotton letter, Nashe says nothing personal to his friend. I made up some quips: “Nashe does not say, ‘Thanks for bringing that cash to me in the Fleet,’ or, ‘Hey, it sure was fun partying on Accession Day,’ or anything like it.” Anon counters by saying that Nashe would not have said those specific things. I concede, he is right, and I will fix my offhand quips. But I also added, “or anything like it.” The point remains: Nashe says nothing personal to his friend. Even “Do you plan to be in London soon?” would impress me as personal. I still think the letter is literature.

Not Just Book Reading

Anon argues that if a real Nashe had been at Cambridge for six to seven years, he could have read enough sources to produce Anatomie of Absurditie. There is far more involved, however, than just book reading. As noted in OV,

As a teenager, Nashe further managed to become proficient in the euphuistic writing style, which he employs while echoing dozens of textual constructions, references and even a misspelling from his predecessors George Pettie, John Lyly and Robert Greene [all Voices], as cited time and again by McKerrow. Euphuism is based on voluminous reading and memorization, and even if one had the requisite resources, executing that dense and ornamental style is exceedingly difficult. How did Nashe do it?

Throughout the remainder of his 400 pages of notes on Nashe’s texts, McKerrow expands the above list of sources significantly. “Nash seems…to have been well read in…the burlesque poets of Italy.”* “[H]e was widely read in the classics and was well versed in…Italian satires…and the work of Rabelais.”* Flowing naturally from our context, from “The extent to which Shakespeare was familiar with Francois Rabelais’ Gargantua and Pantagruel…it becomes evident that Shakespeare was actually quite well read in the work.”* Nashe also drew from du Bartas’ Second Semaine. Yet one critic was loath to conclude that he knew French: “…I cannot learn that the passage had been translated into English so early, but I do not think that is any reason for supposing that Nashe had read the work in the original French.”* He’s right: In the orthodox context, there is no reason for such a supposition.

…Nashe knew the works of numerous other English writers, too. In his introduction to Greene’s Menaphon, he judges the works of Geoffrey Chaucer, John Lidgate, John Gower, Robert Greene, George Gascoigne, George Turbervile, Arthur Golding, Thomas Phaer, Abraham Fraunce, Thomas Watson, Thomas Newton, Gabriel Harvey, Edmund Spenser, Matthew Roydon, Thomas Achelow, George Peele and William Warner. Some of these works weren’t even published yet. Regarding Roydon’s “A Frends Passion for his Astrophel,” “he must have known it in manuscript, since it was first published, anonymously, in The Phoenix Nest anthology of 1593.”*

Nashe did not merely consult sources, either; in many cases, he knew their content by heart. Steane wrote,

Almost every page of McKerrow’s notes on the texts contains its allusions to Ovid, Virgil, Horace and other standard classical writers[, as well as to] Spenser, Marlowe, Greene, Lyly, Sidney, Thomas Watson, William Warner and Sir John Davies…. these were no doubt the standard authors of the educated Elizabethan, but Nashe had them in his system, not just in his notebooks, for the allusions come (in his own phrase) “thick and three-fold” and clearly a part of his mind.*

In other words, Nashe did not merely know of these sources or quote from open books; he had memorized them so thoroughly that they contribute to complex, intertwined allusions incorporated into his stream-of-consciousness writing. Density and complexity of allusions, an extremely rare authorial trait, is one of the hallmarks of Shakespeare.

Nashe never explains how he obtained access to all these books, which were expensive and hard to locate. He mentions no tutor. He mentions no patron’s library. He was too poor to afford books. He lived in London, far from the Cambridge library.

My Nashe chapter is 200 pages long. It contains many observations showing that Nashe by age 21 had the mind of the Earl of Oxford at age 39. It is all I can do to refrain from quoting more of it to you. To answer Anon: No, I do not think a recent college graduate could have possessed all this knowledge and composing talent, which just happens to be along the lines of Lyly, Greene and Shakespeare.

Recognizance

Anon makes one substantive observation, namely that a “recognizance” is a court order implying that Nashe had been previously arrested. Anon went down a long trail of investigation to figure that out, for which he deserves cheers and credit.

It is absurd, however, to imply that anyone who read Hutson’s page-and-a-half article of 1987 (as I did; OV quotes from it twice) would come away with that insight. Hutson herself simply printed the word “recogn” from a marginal note in the Repertory for the Court of Aldermen and called the order a “recognizance.” She did not comment on the implication of it. In fact, none of the full-length biographies of Nashe highlighted it, and none of the over 200 sources I accessed for the Nashe chapter — to my recollection — explicitly made the case. Had anyone done so, I would have addressed it.

Anon seems to excuse all Nashe scholars writing before 1987 from missing the implication of the marginal note “recogn” in the state record, but that “pass” is unwarranted. For 400 years, the abbreviated word was right there, for all scholars of Nashe to see. So, on this fine point of law, it seems that everyone before Anon has been unaware and deficient. If a trial lawyer or professor of criminal law had missed the implication of “recogn” in Hutson’s brief piece, Anon might be justified in adding this lack of knowledge to a list of my insufficiencies, but neither I nor Anon is an expert at everything.

Anyone who thinks a clerk’s marginal note negates the entire case that the Earl of Oxford is behind the oeuvre of Thomas Nashe is welcome to that opinion. Because there is no arrest record or release record for Nashe (as there is for Gabriel Spenser, Robert Shaa and Ben Jonson), I think there is room to doubt whether the demand for him to “personally appeare” means that authorities previously had the body of an honest-to-god Nashe in custody.

(We might ask: Are all records in the Repertory perfectly consistent with respect to known custody vs. non-custody? Did the clerk have certain knowledge about the matter, or did he make a supposition about the meaning of a call for Nashe to personally appear?)

Anon pushes a point about the recognizance three different ways, all in a row, as if we aren’t smart enough to get it the first time:

One problem in Robert Prechter’s treatment of this information is that he deals with the recognizance separately from George Carey’s letter. These two documents corroborate each other…. In his section on the recognizance, he doesn’t mention George Carey’s letter at all. In Robert Prechter’s section on Carey’s letter, he doesn’t mention the details of the recognizance….

Two replies: (1) The documents do not corroborate each other. As explained above, the stylistic aspects of the Carey letter belie the whole scenario. (2) My organization of material is not a problem. I treated a long list of items, and each one gets covered. There is no reason to meld two discussions in this instance. Nashe’s biography is one giant meld, necessitating its dissection item by item.

Even when proffering his best point, Anon plumbs the depths of pettiness to imply shortcomings on my part. You should hope he does not come after you.

The Single Eyewitness and Whom He Saw

Anon cites Hugh Broughton’s letter to Lord Burghley as evidence Nashe existed. That letter is no revelation. I saved that topic for last in my paper precisely because it is the only record indicating that someone saw or met Thomas Nashe. (Even Gabriel Harvey never saw him, either at Cambridge or afterward.) As my paper noted, aside from that single exception, “no person, court or office left a letter, a memo, a memoir, a bill, a payment, a lease, a contract, a grammar or prep school record, a legal proceeding, a marriage record, documentation of children or a burial record attesting to the existence of Nashe.” No wonder Nashe himself confesses five times (as quoted in my paper) that his person is invisible to the world!

In his letter, Broughton tells Burghley he had been insulted by three people at Croydon, including Whitgift’s “Nashe gentleman.” I concluded that Broughton wrote to Burghley (among all the people he could have chosen) in hopes that he would do something about his son-in-law.

My conclusion about Broughton relies upon an idea that may seem strange to people: that Oxford occasionally went about role-playing in real life. Quite naturally, Anon is dismissive of the idea that Oxford might have posed, in clever fun, as one of his personae.

But I think my articles on George Peele’s note to Lord Burghley of 1596 (see links in Appendix 3 and further discussion below) prove he did exactly that. The note is chock full of Shakespearean terms and expressions, including obscure ones. Peele’s father’s records indicate that George had no children, whereas the note refers to its courier as “my eldest daughter,” indicating that the writer of the note had at least three daughters, as Oxford did. At that time, Oxford was spending a lot of time with his eldest daughter, Elizabeth Vere, who was Burghley’s granddaughter. When Oxford signed the note, “George Peele,” he was playing a role, and his daughter and his father-in-law would no doubt have delighted in it.

The idea, then, that Oxford may also have entertained the Whitgift household in such a way — including staging a humorous play depicting, of all people, Lord Burghley, his two sons and his boisterous son-in-law — cannot be summarily dismissed as “unfounded,” “unnecessary” and “not…plausible.” The more one examines the context, the more it comes to life.

Cambridge Records and a Missing Pre-University Education

I wrote, “As the most socially prominent alumnus of St. John’s, Oxford would likely have been permitted to arrange for a few records at Cambridge suggesting the existence of a student named Thomas Nashe….” I did not say I had physical evidence that is what happened. Numerous indications that Oxford wrote under the name Thomas Nashe led to a conjecture.

People falsified records about Shakespeare so expertly that to this day, the vast majority of English professors still believe in them. It will not do for Oxfordians, of all people, to assert that the idea of falsified records with respect to a pen name of Oxford’s is far-fetched.

Anon reports, “Males who attended [college] varied in age from 14 to 18 as, again, performance at preceding levels was the most important factor.” There is no record whatsoever of Nashe’s “performance at preceding levels,” which we would likely have if Nashe had been an exceptional student somewhere.

I pointed out what I thought were anomalies in various claims about Nashe’s time at Cambridge. Anon spends pages establishing that one can accommodate the seemingly conflicting claims of Nashe’s time at Cambridge:

It’s important to note that one’s matriculation does not necessarily record the date that one arrived at Cambridge or began one’s studies. … According to McKerrow, it seems to have been common for a student to spend some interval of time at a college before participating in the matriculation ceremony.

In other words, instead of entering Cambridge upon matriculation on October 13, 1582, a real Nashe could have arrived in the “winter of 1581-82.” I am content to accept that possibility, and I will amend (thank you) a paragraph about temporal anomalies from my book.

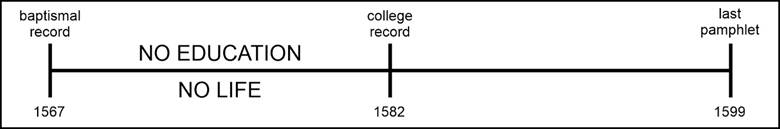

Honestly, however, I don’t care about this discussion because there is no evidence that “Nashe” arrived from anywhere. The possibility that a real Nashe could have arrived at Cambridge a few months before the university entered a record of him makes no difference with respect to the utter lack of a previous life. In short, my observation was, and still is, this:

As I pointed out in OV and the TOX paper, we have pre-university education records for Christopher Marlowe, Thomas Lodge, Ben Jonson, William Gager and George Peele but not for my two suspected pseudonyms: Greene and Nashe.

I noted in OV that McKerrow conjectured of Nashe, “we may suppose that he received his early education from his father.” Because no one has found records of an education for Nashe, McKerrow did the sensible thing and seized upon a possibility. But he did so because he was locked into the idea Nashe was real and that he had entered Cambridge. What else could he conclude?

Anon suggests we should all accept McKerrow’s conjecture. Why? What we know of William Nayshe doesn’t fit well with the idea that he was equipped to teach his son pre-university-level reading, writing, math and Latin. He was a churchman in a fishing village and then a small-town rector. William’s other offspring, a daughter and elder son, lived locally with their families, making no impression upon history, suggesting that they did not benefit from the caliber of education being imagined for Thomas. Regardless, it is all supposition, undertaken because there is no evidence to support any of it.

^A Bogus Early Life

Forget an education; there is no record of a life for Nashe between baptism and college. Nashe himself tells us nothing specific about his early life. Listen to one of his biographers (Nicholl, in the New DNB) buy what Nashe is selling. He writes, “Memories of rural childhood surface in Nashe’s writings.” Really? Tell us! Here is the only passage he quotes in that regard, from Terrors of the Night:

I have heard aged mumping beldams as they sat warming their knees over a coale…. When I was a little childe I was a great auditor of theirs, and had all their witchcrafts at my fingers endes, as perfit as good morrow and good even.

Observe that Nashe makes no mention of his age at the time, who the women were, or where these sessions took place. Yet biographers lap it up. And they do so without asking the simplest of questions, such as:

What the heck is a minister’s son doing listening time and again to a coven of self-professed witches?

And

Is the idea that covens of witches were operating at that time or in that area — or anywhere, for that matter — historically accurate?

(No. Women were persecuted as individuals.)

Wake up. This is not a real Thomas Nashe talking. It is the Earl of Oxford. Conjuring up a nearly identical image, Lady Macbeth (III,iv) entreats her husband not to believe scary tokens that “would well become/ A woman’s story at a winter’s fire,/ Authorized by her grandam.” When you search Shakespeare’s terminology, you find that Hecate, the goddess of witchcraft and head witch in Macbeth (III,v), calls her minions beldams. Nashe’s beldams have a burning coale; Shakespeare’s have a burning flame. Nashe says he has their spells “at my fingers endes.” Maria in Twelfth Night (I,iii) remarks, “I have them at my fingers’ ends.” Nashe uses the word auditor. What does Puck say in A Midsummer Night’s Dream? “I’ll be an auditor;/ An actor too….” That’s Nashe in a nutshell: a spirit who is an auditor and an actor. Not to mention that Shakespeare uses 18 witchcraft’s, 20 good morrow’s and a dozen good even’s!

Oxford as “Shakespeare” puts tales into plays. His pen name “Nashe” pretends to live them.

I found these linguistic connections in a brief time. Try it yourself, on any colorful passage in Nashe’s canon. To wit: I just opened Terrors, scanned the dedication for ten seconds, and found “Deare Mistris perswade your selfe that no frowning misfortune….” A quick search of Shakespeare turns up “Do you persuade yourself that I respect you?” from Measure for Measure (IV,i) and “hard misfortune” and “sour misfortune” from Lucrece and Romeo and Juliet (V,iii), respectively.

Tobin was not kidding when he said, “Nashe is so much a part of the fabric of Shakespeare’s works that it is not too much to say that Shakespeare without Nashe and his works would not be Shakespeare.” His only slip was to understate the connection.

^Robert Mills Helps My Case

Anon refers to “The Manuscript poem of Richard [sic] Mills, which provides details about the Cambridge student play, Terminus & non terminus, which Thomas Nashe and Robert Mills had written together.” That is an assumption. Mills does not say that he and Nashe wrote a play together. He writes, “Never an howre did pass but some toy still we devised.” One would think that “we” refers either to the person to whom he is writing, John Finet, or to students in a general sense. He does not name Thomas Nashe.

It is entirely reasonable for orthodoxy to put the Mills manuscript together with the comment from “Richard Lichfield” accusing Nashe of having been involved in the skit to conclude that both Mills and Nashe were involved. But even here, our heroes are living in print, and one must dig to discover what is really going on. Bear with me as I map it out.

Scholars have defaulted to ascribing The Trimming of Thomas Nashe to Richard Lichfield, a Cambridge barber. The pamphlet warriors are bamboozling them. Nashe had mock-dedicated Have with you in 1596 to the Cambridge barber, and in 1597 the “barber” replied with the pamphlet. When I was a young buck working near Wall Street, I used to get my hair cut at a below-ground shop. The guys who worked there were fine fellows, but none of them were capable of writing anything as learned and erudite as The Trimming. Nor did Lichfield, who lived another 33 years, write anything else.

I looked into the matter and figured out that the true author was Joseph Hall, as reported in my article for the De Vere Society Newsletter, January 2023 (link in Appendix 3). Hall attacked Oxford twice anonymously, once shortly before and once shortly after he issued The Trimming under the Lichfield allonym. In the other two pamphlets, Hall berated Shakespeare’s Venus and Adonis and Nashe’s Pierce Penilesse and Valentines, attributing them all to the same moniker, Labeo. By that fact alone, I concluded he knew full well that one man (Lab-E-O) was behind both pen names. That is why, in The Trimming, Litchfield puns relentlessly on true (truly = Vere in Latin) and bids Nashe to “apply it to your selfe.” I quoted the passage in the TOX paper. So, when “Lichfield” says that “Nashe” was involved with Terminus, Hall is saying that Oxford was involved with Terminus.

Ironically, only in my context does Mills’ testimony link authorship to the same man. Here is why: Mills recounts that in the play he was an actor, indeed the very Lord Non Terminus, who would frown at the grave Lord Terminus and smile at a buffoon named Doleta, who were two characters in the play:

See how I sitt in royall Chayre enthronissed emprer:

Se how I frowne lyke a prince agaynste Lord Terminus Ireful:

Se how I smyll to see the Jestes of merye Doleta:

Goulden dayes, when Lord Non Terminus hyghly tryvmphed….

In OV and in an article for The Shakespeare Oxford Newsletter (Fall 2024; link in Appendix 3), I proposed that Straunge Newes out of Calabria (1587), which purports to recount the astrological prognostications of one John Doleta, is a lampoon, written by Oxford, of John and Richard Harvey’s astrological predictions. If Oxford wrote the Doleta pamphlet in 1587, wouldn’t he be a prime candidate for having been one of the composers of the skit featuring Doleta that same year?

Would a real Thomas Nashe — or any other Cambridge student — at the tender age of 19 (the baptismal record for “Thomas Nayshe” is dated November 1567) have cared to make fun of the Harveys? I think that idea is ridiculous on the face of it.

In fact, in this context, Anon’s own argument makes that scenario impossible. Gabriel Harvey, whose time at Cambridge overlapped Nashe’s supposed time there by three years, claimed in 1590 that he had never heard of Thomas Nashe. I considered his statement supporting evidence that there was no Nashe. Anon countered, “It is entirely possible that neither Richard or Gabriel Harvey had ever heard of Thomas Nashe before reading Thomas Nashe’s Preface to Greene’s Menaphon (1589).” Anon also claims that Nashe co-wrote Terminus, a skit so infamous that he ties it to a decision made by the university the following year to ban such entertainment. By his own case, a real Nashe could not possibly have written a skit featuring “jests of Doleta,” if those jests were directed at the Harvey brothers, because obviously Gabriel would have known Nashe existed if that had happened.

An “out” for orthodoxy might be that Doleta’s book is not a jest on the Harvey brothers, nor did Terminus make fun of them. Harvey himself, however, complained of just such treatment —being lampooned in plays — only a year after his Audley End speech: “Gabriel Harvey wrote in 1579 to the poet Spenser, complaining that his friends were (figuratively speaking) thrusting him ‘on the stage to make tryall of his extemporal faculty and to play Wylson’s or Tarleton’s parte’…” (DNB, Robert Wilson). Obviously, Thomas Nashe at age eight did not conduct those earlier skits. Did some unknown, young Cambridge student take over the task for some reason in 1587, or did Oxford simply continue torturing his nemesis in the same manner? I think it fits neatly into my context to surmise that Oxford was at Cambridge in 1587, amusing the pants off younger Cantabs by mocking one, two or perhaps all three Harvey brothers, the eldest of whom, Gabriel, had annoyed Oxford since 1578.

Our context makes clear why Harvey declared he had never heard of Nashe. Harvey would have associated Oxford with the skit, not a student named Thomas Nashe. He truly did not hear the name Thomas Nashe until 1589 (nobody did), and now we have a sensible explanation for that fact.

Anon repeats the Folger’s comment, “Rita Lamb has recently made the argument that parts of Terminus & Non Terminus may survive, as a palimpsest, inside Summer’s Last Will and Testament.” In the linked article (https://www.members.tripod.com/sicttasd/aside.html), however, Lamb does not even mention Terminus. Her closest comment is, “I think…large parts of SLW, like the Anatomy, were written while Nashe was still at university.”

Nevertheless, let’s pursue the idea that Nashe mined from his own Terminus for Summers Last Will. Obviously, Nashe’s orthodox biographers would see that as a fine fit. On the contrary, it far better fits my case because Summers Last Will is not about some topic fitting Thomas Nashe, Cambridge terms, the Whitgift household or even Gabriel Harvey. As noted above, it is about William Cecil willing various things to his sons Robert and Thomas while leaving nothing to his son-in-law, Ver, all in ways that match Lord Burghley’s actual will. Because Summers Last Will is about Oxford’s family, and if you believe that bits of Terminus are in it, the sensible conclusion is that the Earl of Oxford had a hand in writing Terminus at Cambridge in 1587.

^Nashe’s Travels

There is more to consider about Anon’s discussion of Mills. He makes this statement:

Robert Mills became a grammar school teacher in Stamford, Lincolnshire. …Andrew Hadfield noticed that this helps explain Thomas Nashe’s trip to Stamford in 1595:

He appears to have visited friends in the country, such as his co-author from his student days, Robert Mills, who lived in Stamford Lincolnshire. (Nashe refers to the journey there in Have with You).

Since quibbles are the order of the day, we should note that Nashe does not say he visited anyone, much less Mills, and he doesn’t say he took a “trip to Stamford.” Rather, he had described hexameters as a “drunken staggering kind of verse, which is all up hill and downe hill, like the way betwixt Stamford and Beechfeeld.” He thus depicts having traveled on a road near Stamford. Regardless, Anon omits my assessment in OV of this very valuable information. I wrote,

An endnote of Nicholl’s reveals why Oxford would have traveled to that area: “Lord Burghley’s family seat, Burghley House, was a few miles from Stamford.” Actually, the distance is just a hair over a mile. Oxford was visiting family.

This is a good place to point out that Thomas Nashe’s travels and locations could have confirmed his corporeal existence. It would be simple as pie for Nashe’s biography to have contained the tiniest bit of history that would instantly confirm the case that he is a real person. For instance, he could have convincingly described a trip to Portugal at a time when Oxford was known to be elsewhere, especially if records from Lisbon confirmed he was there. That’s all it would take. Edmund Spenser, for example, spent most of the 1580s and 1590s in Ireland, where he served Lord Deputy Arthur Grey and bought estates. Thomas Lodge sued members of his family, sailed to Brazil, obtained a medical degree in France, and returned to England to open a medical practice. You cannot make a pseudonym out of either person.

Nashe’s biography has no such solid elements. On the contrary, OV offers a table showing that Nashe’s travels fit into gaps in Oxford’s biography. Some of Nashe’s implied travels fit Oxford as opposed to Nashe, such as when he uses sailing terms and claims knowledge of Italy. Our critics do not address any of that.

At one point, Anon does a good job of establishing that Nashe’s wanderings in 1597-99 following the Isle of Dogs incident form a coherent narrative. But I think Oxford was doing the traveling while playing a role in print.

^Handwriting

The Folger Library recently posted an announcement about marginalia in a copy of An Almond for a Parrat (1590), attributing the handwritten notes to Thomas Nashe. The most important sentence in the report for our purpose is this one:

Nashe made these corrections in his best, most legible hand — quite different from the hand he employed in his letter to William Cotton and, apparently, in manuscripts he submitted to the press that compositors struggled to read.

If Thomas Nashe can be allowed “quite different” hands, then the Earl of Oxford can be allowed them, too. That is especially true if he was role-playing.

If one were to scramble 50 handwritten documents of the day, I doubt a handwriting specialist would match the careful writer of the paraphrase of Ecclesiasticus, attributed to Nashe at college, to the sloppy writer of the Cotton letter. I also doubt a specialist would match the Earl of Oxford’s handwriting from the Doge’s palace with that in his tin letters. If handwriting analysis were to fail to link Nashe to Nashe and Oxford to Oxford, then it cannot be used to distinguish Oxford from Nashe. A selectively applied, future handwriting exercise with a negative result would not confirm anything.

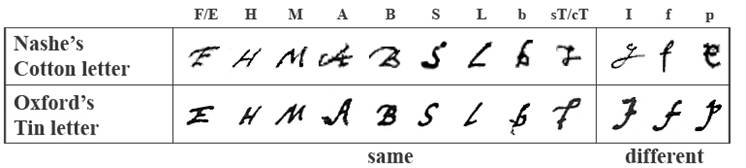

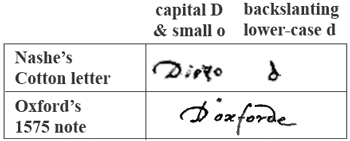

As it happens, I did look at the writing in the Cotton letter, because it struck me that it had the hardscrabble look of Oxford’s tin letters. Both sources are difficult to read; the Cottom letter is too short to provide more than a few capitals; and I do not have my own forensic handwriting lab. But I did find some close matches as well as some dissonance. I do not claim this exercise proves authorship, but I do think it allows that Oxford wrote the Cotton letter.

I also found a capital D and a small, isolated o that fit nicely, from the 1575 permission slip that Oxford signed in Venice:

Critics will say, “That doesn’t prove anything!” But it does. It proves that I have looked into the matter more than they have. Anon knew it, too, because it’s in my chapter.

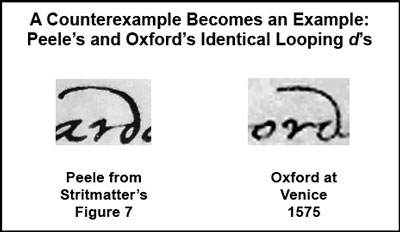

My articles on George Peele (links in Appendix 3) show that Oxford’s most elaborately formed letters appear identically in George Peele’s writing, fitting no other items in W.W. Greg’s book. An experienced handwriting analyst challenged me with the objection that Peele’s backsloping d is absent from Oxford’s writing, so Oxford could not have written Peele’s note. Although handwriting analysis is not remotely my field, I quickly located the letter formation that the challenger said didn’t exist. It is on the slip of paper Oxford signed at the Doge’s palace in Venice, with a preceding r creating another dual letter combination that is virtually identical:

None of this was enough for said critic. He protested that, well, a few other letters, such as Peele’s and Oxford’s s’s, are different! Are we to think that a few letter differences disprove single authorship? No one’s writing is consistently identical. I myself write s’s in two completely different ways.

The point is that no handwriting study by me is going to convince entrenched critics of anything. Asking for one is insincere. Our critics would just use it to argue with me. Their intractability is no different from Stratfordians’.

Wouldn’t it have been a wonderful thing had our handwriting specialist confirmed that Oxford wrote Peele’s note? Oxfordians would have a united front on the smokingest gun we have.

^Margaret Nashe’s Will

It is enlightening to be informed that Rita Lamb found that Margaret Nashe’s will was written by an identifiable town clerk and relative of hers. I did not know that. I nevertheless already proposed that if the will is genuine, it contains a problem because it left Thomas household items including a featherbed. I proposed that Margaret’s bequest fit a local Thomas better than a budding writer who was living 143 miles away in London.

Anon offers several scenarios (with one “imagine” and five “possibly”s) to account for why Nashe’s mom, with the blessing of his elder brother Israel, the executor of the will, left him a featherbed. I do not think the argument holds up.

Margaret’s will was drawn up on December 2, 1589. The date is important because Nashe’s biographers tell us that throughout the second half of 1589 and into 1590, Nashe was working closely with the Archbishop of Canterbury, whose preferred residence was at Croydon, just south of London.

The timing of these pamphlets, as we have already seen, challenges the idea that Archbishop Whitgift would have chosen a real Nashe as his mouthpiece in the first place. It also challenges the idea that Margaret was leaving stuff to her son the writer. Nashe issued A Countercuffe given to Martin Junior under the name Pasquil in August 1589 and followed up swiftly with Pasquils Returne to England and Marphoreus’ Martins Months minde in late 1589, and then The First partes of Pasquils Apologie and Cutbert Curry-knave’s An Almond for a Parrat in 1590. Nashe’s Anatomie had been registered in August 1589 as well, but it did not come out until late 1589 or early 1590, for the obvious reason that “Nashe” became sidetracked fighting Martin. The point is that throughout this period, Nashe was demonstrably busy in London, far away from where Margaret was buried on December 10 in Lowestoft. If her son Thomas had been away from home for years and was at that time in London conducting state business, his family surely would have figured he wasn’t close enough to pick up a featherbed on Thursday, much less cart it all the way home.

I am pushed toward the conclusion that if William and Margaret Nayshe had a son Thomas, he was living locally and was not the writer. That conclusion is hardly more speculative than spinning “possibly”s about why Margaret was unaware that her son was miles way according to the very biography that our critics are trying to defend.

It would be fortuitous if a researcher were to find evidence of a Thomas Nayshe living in the East of England in the 1580s and/or 1590s. That would help sever the two Thomases for good.

Replies to Six Dubious Conjectures

Anon quotes Andrew Hadfield saying, “Nashe is now recognized as a pioneering playwright as well as a prose writer who collaborated with Shakespeare and Jonson early in their careers, as well as with Marlowe.” Anon adds, “Besides his involvement in writing The Isle of Dogs with Ben Jonson, Nashe possibly also contributed to Jonson’s The Case is Altered.”

I don’t know of any hard evidence for Nashe collaborating with Shakespeare, or with Jonson on The Case Is Altered. The idea of collaboration with Marlowe is based on the title page of Dido. Acts III-V of the play are Shakespearean in language, ideas and characters, implying Oxford wrote them. Collaboration was not involved; Oxford simply finished a play that Marlowe had been working on before he was murdered, and he put Nashe’s name on it (Prechter, TOX, 2025; link in Appendix 3). Nashe informs us that he wrote only the first act of Dogs and then handed it over to someone else to finish, indicating no collaboration there, either. The Case Is Altered has Shakespearean elements, and I think Oxford used the name of the pre-famous Jonson as an allonym, which accounts for why “Nashe” promoted the play and Jonson later disowned it. All these ideas are discussed at length in OV.

Anon asserts that Nashe could have written not just unpublished plays but also unknown plays because he writes to Cotton of an “after harvest I expected by writing for the stage and the press.” The idea of Nashe’s prolific, non-extant playwriting is a massive conjecture supported by no evidence of any kind, documentary or circumstantial.

Because I am not stuck in the standard paradigm, comments like that immediately prompt me to think, “Is there a husbandry metaphor like that in Shakespeare?” Sure enough, Shakespeare uses the two highlighted words, also metaphorically in connection with writing, in the dedication of Venus and Adonis: “I shall…never after ear so barren a land, for fear it yield me still so bad a harvest.” Nashe’s biographers do not find such connections because they are not looking.

Matching a public idea from Oxford to private correspondence from Nashe makes sense in my context: They came from the same mind.

On the law: Anon says, “Prechter compiles a list of phrases in the letter that pertain to the law,” but in fact the list was compiled by E.D. Mackerness in 1949. Nashe was expressing a legal mindset, as he had done in Strange Newes, which, as Hibbard put it, “is conceived of in terms that recall…those used in a court of law.” A legal mindset fits Oxford better than Nashe. Using a variation of the Mermaid Tavern argument, Anon argues that Nashe might have learned some law. But we know Oxford did.

Anon spends a lot of space arguing that a real Thomas Nashe could have made money in various ways. Anything is possible, but all we have from him are a short play, part of a play and 8 pamphlets. Even if Nashe is to be credited with most of the anti-Martinist pamphlets, the total is scant output for a real, full-time writer and would not have supported the man of orthodox biography. McKerrow agreed:

Certainly, Nashe could never have existed by the sale to the booksellers of those of his writings which are now known to us: by far the greater part of his income, small as it was, must have come to him from other sources.

What sources are those? Nashe does not reveal any.

Anon supposes that Nashe was living off others, such as Robert Cotton, at whose home he wrote Terrors of the Night. Once someone accepts the notion that Nashe was real, then all kinds of inferences suggest themselves. The same thing is true of Will Shaksper as Shakespeare: He must have been educated; he must have made money writing plays; he must have had patrons; he must have learned about Italy from travelers. Even the idea that Whitgift must have paid Nashe for the 1592 entertainment is an assumption. All we know is that Nashe’s name is on the entertainment. Because that is all we know, I am allowed to speculate as to who really wrote it.

Nashe mentions Leland in his 1589 preface to Greene’s Menaphon, and a copy of a book by John Leland bears the handwritten name “Thomas Nashe” and marginal notes pertaining to Marlowe’s Faustus. Like much such information, this evidence fits into the biography of Thomas Nashe. It does not, however, contradict the idea that Oxford made the notes while role-playing.

Scholars have proposed that someone added the prose section of Faustus to Marlowe’s original verse. Oxford is a good candidate for having done so because elements such as the introduction of a clown are in Shakespeare’s universe but not Marlowe’s. The Clown’s parts, moreover, mirror aspects of the Shakespeare-precursor play, The Taming of a Shrew. That Oxford made notes about Faustus for use by “Nashe” would hardly be surprising. One wonders if his plan was to add Nashe’s name to Marlowe’s Faustus as it had been added to Dido.

Anon says that Nashe’s mock dedication to tobacco user Humphrey King and a poem put out under the name Humphrey King with a prefacing, unattributed sonnet mentioning “famous Nashe, dear to us both,” show that Nashe was real. They do not. If someone wrote, “famous Twain, dear to us both,” it would not negate the fact that Mark Twain is a pseudonym.

^Jonson’s Remembrance Fits My Context

Remembrances by Charles Fitzgeoffrey (discussed below), an anonymous Parnassus author and Ben Jonson refer to Nashe’s death. According to Anon, these epitaphs confirm Nashe’s real death and therefore his real life.

That is not so. Other writers from 1592 until 1617 referred to the death of Robert Greene, but that does not make him real. They were referring to a persona. Numerous clues, discussed in detail in OV, show that to be the case.

Jonson’s format and words hold clues, too. Consider these key portions of his extensive lines on Nashe:

Ad, charissimam memoriam Th. Nashi amici dilectissimi

Beniamin Jons. Hoc eligidium consecrauit

View here a trophee of that tyrant deathe

And let the obiect strike your melting eyes

blind as the night, when you but read, Here lies

Conquerd by destiny & turned to earthe The man….

Are the format and text familiar? Here are key portions of Jonson’s text on the monument in Stratford-upon-Avon:

Judicio Pylium, genio Socratem, arte Maronem,

terra tegit, populus maeret, Olympus habet

Stay passenger, why goest thou by so fast?

read if thou canst, whom envious death hath plast

with in this monument Shakspeare: with whome,

quick nature dide….

Jonson’s lines on Nashe entreat the passerby to “View here…the object,” implying a physical memorial, like the one in Stratford. Jonson’s “tyrant death” echoes “envious death” on the Stratford monument. His “when you but read” echoes “read if thou canst,” and his “Here lies…The man” echoes “plast with in this monument.” In the first instance, he names “Th. Nashi,” and in the second he names “Shakspeare.” Jonson begins each epitaph with a statement in Latin. The two memorial layouts and the texts quoted are of a kind.

Oxfordians have long concluded that Jonson knew Shakespeare was a pen name, but he never clearly revealed who was behind it. I do not see why his words about Nashe should be construed any differently. On the contrary, the two epitaphs are compatible in referring in like manner to personae of the Earl of Oxford. Far from proving Nashe was real, Jonson’s epitaph neatly fits the case that he was not.

Anon closes by saying, “Jonson’s closing couplet is especially moving.” Yes, it is. That is where he exclaims, using a carefully chosen word, “Farewell, great spirit.”

If I Were Forced to Guess

Critics might try to counter that Jonson could have used his epitaph on a real Nashe as a template for his epitaph on a fake Shakespeare. That idea, however, does not explain why Jonson says, “View here,” in reference to Nashe, when there is no known grave for the man. It seems to me he had a monument in mind.

So, I wonder: Did Jonson compose the manuscript text for a planned monument to Thomas Nashe? The Nashe persona had become so hot by 1596 that people were inquiring into it. Maybe Oxford developed a plot to confirm Nashe’s “death” and solicited Jonson’s help in the matter. The plan never materialized, which is why his epitaph and others remained in manuscript. In 1623, when Shakespeare became hot, Jonson applied their previously conceived gambit, writing similar text for the monument to Shakspeare. Jonson’s epitaph on Nashe ran quite a few more lines, and the rest of his tribute to Nashe may have been a model for Jonson’s praise of Shakespeare in the First Folio.

Had someone constructed a monument to Thomas Nashe in 1601, people today would be making pilgrimages to it after touring Stratford-upon-Avon.

That’s it for Anon. He was by far the toughest of the three to debate. Now for the easy ones.

Anon2 Critiques My Paper

In Part 2 of the critique, a new anonymous writer takes over to level an attack on my TOX paper. He is prone to sweeping accusations and snide remarks:

Before addressing Prechter’s arguments, one question needs to be addressed: why were obvious sources not consulted? In academic papers, especially at university level or for publication, it is standard to include a literature review or at least a discussion of relevant prior work. This was not done here. The ODNB entry for Nashe, for example, or Diana Price’s Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography, considered one of the seminal sources for the SAQ, and W.W. Greg’s English Literary Autographs for Nashe’s handwriting would have been obvious candidates. They contain documented material about Nashe that Prechter fails to mention, and clearly show his education was real, that he was capable of writing at a high level and make a mockery of many of Prechter’s assertions.

What puffery.

Of course, I “consulted” the ODNB on Nashe, as well as the New DNB. Of course, I consulted Diana Price and W.W. Greg, whom Oxford’s Voices cites more than two dozen times each. My Nashe chapter refers to over 200 sources.

I do not need to be lectured that Diana Price summarized evidence of a life for Nashe and that Greg displayed handwritten items by Nashe. My paper took such evidence as a given and offered reasons to reconsider it in a new light. His tiresome reiteration of every item on Price’s “Chart of Literary Paper Trails” takes up space but covers no new ground. It is a partial summary of what every biography of Nashe already tells us.

Anon2 comments on numerous lines in Nashe’s Cotton letter to no negative effect. Sometimes the effect is positive to my case. He reminds us,

As Price writes, “Toward the top, Nashe refers explicitly to his professional activities: ‘an after harvest I expected by writing for the stage & for the presse, when now the players as if they had written another Christs tears, as piteously persecuted by the L[ord] Maior” (Price, 118).

I do not know why he quotes Price just to quote Nashe. Regardless, neither Price nor Anon2 noticed that Nashe’s metaphor of an after harvest, as noted above, shows up in Shakespeare. Should anyone say that their failing to mention that fact makes a “mockery” of their work? No one is omniscient.

Anon2 then shows us pictures of Nashe’s writing and says, “We see Nashe’s signature” in a book. That doesn’t prove anything. The question I posed was, “Who put it there?”

^The Epitaphs Gambit Redux

Anon2 speaks of “Two epitaphs that Prechter ignored,” i.e. the one by Jonson and another by Fitzgeoffrey. I did not ignore them; they were extraneous to the aim of the paper. Four different chapters in OV discuss these epitaphs. As stated there, “Neither remembrance, however, provides any particulars of the man’s life or death.”

Anon2 quotes both epitaphs in their entirety to no effect. Since both epitaph writers could be referring to a persona, their “testimony” of its “death” doesn’t mean anything.

Anon2 says Jonson’s verse is “a straightforward and genuine tribute to a friend.” I agree; I just think he’s referring to the friend by his pen name, as he did with “Shakespeare” in the First Folio. As a thought experiment, let’s replace “Nashe” with “Twain” in Fitzgeoffrey’s text and pretend it appeared in a Connecticut newspaper:

When Death, obeying Jove’s imperial will,

Extinguished Twain’s bright flame, his voice grown still,

She struck him not in strength, but stole away

His pen and tongue — twin bolts of fierce dismay.

Are you immediately tempted to blurt out, “This proves Mark Twain is not a pseudonym!!!!” Of course not. But that is what Anon2 thinks you should do. He thinks it’s obvious you should do it.

^A Massive, Unsubstantiated Claim of One-Way Style Absorption

Anon2 challenges my quoting of orthodox scholars on the linguistic intimacy between Nashe and Shakespeare. He begins by asserting that I am relying upon the Stratfordian dating of Shakespeare’s plays, which I am not. I quoted Stratfordian scholars to the effect that Nashe and Shakespeare share voluminous stylistic parallels throughout both sets of works. I pointed out that Nashe’s biographers cannot explain how it happened, but that does not mean I relied upon Stratfordian dating.

To straighten me out, Anon2 delivers breaking news that Oxfordians have determined that Shakespeare’s plays were written before Stratfordians say. Good to know! To back up that proposition — as if we all haven’t read volumes on the subject — he cites four sources, all modern (such as Stritmatter & Kositsky on The Tempest, 2013), while omitting seminal works such as Eva Turner Clark’s Hidden Allusions (1930) and the quarter-century of work by Ramon Jimenez, who dated Oxford’s first play to 1562.

All this worthless prelude leads to his big conclusion: There is no “problem” here because “Shakespeare came first.” That’s it. He wipes his hands as if we’re all done here.

Apparently, we are supposed to join Anon2 in assuming that an independent Thomas Nashe memorized Shakespeare to the point that he echoes him throughout his works. It sounds good rolling off the tongue, but that scenario is impossibly far-fetched. Here’s why:

Some of Oxford’s plays were acted in the late 1570s, when Nashe was a boy. Most of Oxford’s plays were acted at court, where the Nashe of orthodox biography would not likely have been admitted once, much less to every play. Not to mention that even if he had seen the plays acted, it is hardly reasonable to infer that he could have memorized them all on the spot. Consider further that during the first half of Nashe’s writing career (1589-1593), no Shakespeare plays were published. In 1594-1597, only six of the Bard’s plays came out, all anonymously. The first play in Shakespeare’s name came out in 1598, the year Nashe composed his last pamphlet. Where did Nashe get access to 30 unpublished plays? There is no reason to believe that manuscripts of them were circulating and plenty of evidence indicating they were not. Oxford kept writing plays until 1604. How did Nashe’s linguistic proclivities get into them?

Orthodox scholars are amazed at the overlap between Shakespeare and Nashe even while believing that both personae were real people living and working at the same time, a situation that could theoretically support a face-to-face relationship. Because Oxford started writing decades before Nashe debuted, however, the overlap is, contrary to Anon2’s blithe attempt at justification, even more difficult to explain.

Let’s try to make something up (“That’s the ticket!”) and see how it flies. Perhaps the Earl of Oxford welcomed a 21-year-old Nashe into the study at his home and let him camp out there for a month to read and take notes on all Shakespeare plays written before 1589, after which he let him come back to read every new play as it was written so that he could take notes on them. Oxford, in turn, memorized all Nashe’s works so he could borrow language from them for plays written after Nashe stopped writing in 1598. Unfortunately, there is no evidence for any such real-life relationship. On the contrary, Nashe’s name is absent from Oxford’s biography. Several of Oxford’s secretaries are known, and they left traces indicating they were real people. Several members of Oxford’s entourage are known, too. Nashe’s name never appears among either group. If Oxford was constantly associating with a real Thomas Nashe, it would likely have been recorded somewhere.

Far-fetched scenarios without evidence are the stock-in-trade of Stratfordians. We should not let blasé apologists for Nashe’s unlikely biography get away with them.